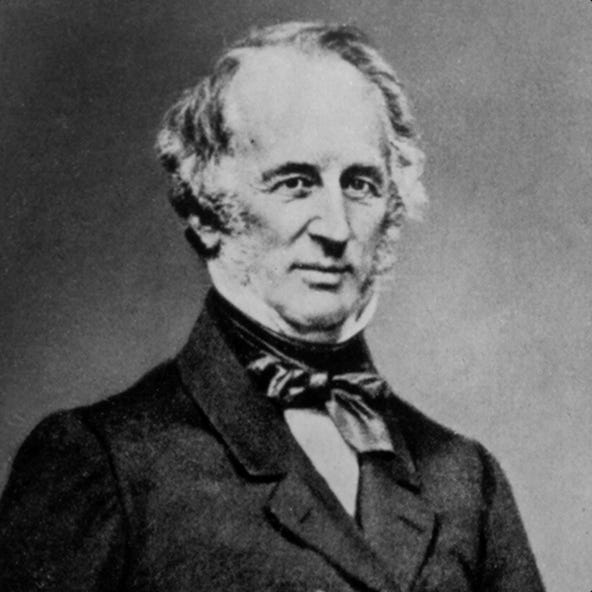

Cornelius Vanderbilt was a ruthless businessman, a “robber baron” who made his money in shipping and railroads. He died in 1877 and left a fortune of over a hundred million dollars, making him the wealthiest person in the United States at the time.

Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877)

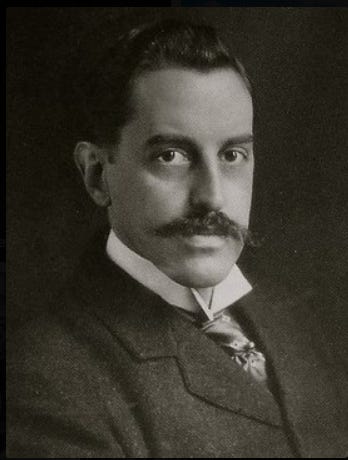

His grandson George Washington Vanderbilt II inherited a $10,000,000 share of the family fortune and used half his inheritance to build the largest privately owned home in the United States: the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina.

George Washington Vanderbilt II (1862 – 1914)

Biltmore house, Asheville

Biltmore House at Christmas time

George Vanderbilt II wanted his house to look like a French chateau. He and his architect Richard Hunt visited several châteaux in France to gather ideas before they began building Biltmore House in 1889.

The name “Biltmore” is a combination of the Dutch “De Bilt” (the family’s ancestral home region in the Netherlands) and “more” (Anglo-Saxon “moor” – meaning rolling or open land).

The house consists of two hundred and fifty rooms, including thirty-five bedrooms for family and guests, forty-three bathrooms, sixty-five fireplaces, and three kitchens, with the main rooms situated on the ground floor.

At a time when most homes relied on gas lighting, candles, or oil lamps, Biltmore House was one of the first to be wired for electricity, a result of Vanderbilt’s friendship with Thomas Edison. The house was one of the most technologically advanced residences of its time, it boasted an Otis elevator and an indoor swimming pool with underwater lights.

About 1,000 workers and sixty stonemasons worked for six years to build Biltmore House, using an on-site brick kiln and woodworking factory. The construction reportedly cost five million dollars, the equivalent of a hundred and fifty million US dollars today.

Biltmore House is surrounded by seventy-five acres of formal and informal gardens designed by renowned American landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted.

George Vanderbilt II had a taste for fine craftsmanship. To make the décor historically authentic he made many overseas trips to purchase art for his mansion. He amassed a vast collection of over 92,000 pieces of art: antique furniture, monogrammed linen napkins from Paris, velvet upholstery fabrics, sixteenth century Flemish tapestries for the Tapestry Gallery and Banquet Hall, two small French impressionist paintings by Renoir, paintings by Whistler and Sargent, and many prints by Albrecht Dürer.

The Tapestry Gallery

The Banquet Hall

The Library

The Billiard Room

Edith Vanderbilt’s bedroom

George Vanderbilt’s bedroom

The Biltmore Estate, Asheville

George Vanderbilt had a strong interest in horticulture, forestry, and scientific farming. He fell in love with the Blue Ridge Mountain area and purchased around 125,000 acres of woodland and farmland to create a self-sustaining working estate. He transformed the overexploited woodland into a lush natural landscape, with formal and informal gardens, water features, and nature trails to emulate the feel of a European country estate and the ambiance of a natural park.

George set up a forestry program managed by experts, and a model village for the workers who built the estate. Biltmore Village was a self-sustaining community with shops, a post office, a school, and a church.

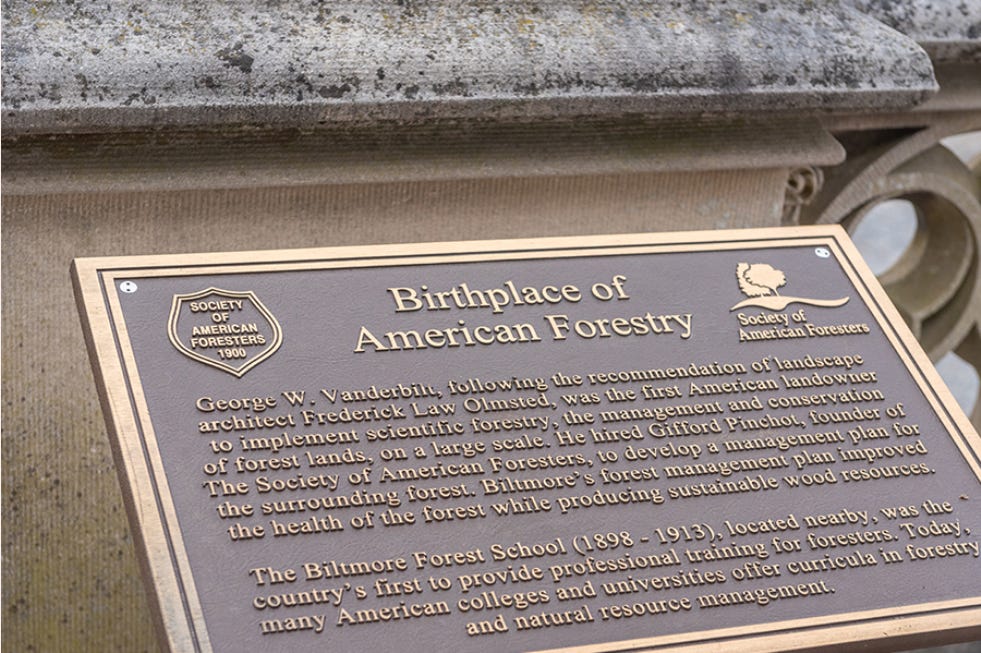

Biltmore became the first professionally managed forest in the United States. Gifford Pinchot served as the chief forester at the Biltmore Estate from 1892 to 1895 and turned the deforested landscape into a productive timberland with a planned forestry program, the first of its kind in America. In 1898 Pinchot became the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service. Vanderbilt and the estate’s first forestry supervisor Carl Schenck, later established the Biltmore School of Forestry on the estate.

Today the Biltmore Estate consists of 7,000 acres with approximately 4,500 acres of planted forests. The timber is harvested and sold to provide financial support for the estate and cover the running costs and wages of fifteen hundred members of staff.

In 1898, George married Edith Stuyvesant Dresser. They had one daughter, Cornelia Stuyvesant Vanderbilt, who was renowned for her eccentricity. George died of heart failure after an appendectomy at the age of 52.

Cornelia, as a toddler, with her mother Edith, c. 1902

Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt, (1873-1958) and her daughter Cornelia Vanderbilt, (1900-1976)

In 1915, to honour George’s wish to preserve his forest for the public’s enjoyment, his widow, Edith Vanderbilt, sold 87,000 acres of forest to the federal government for a nominal sum. George’s gift created the nucleus of Pisgah National Forest, the first national forest in North Carolina and one of the earliest national forests in the eastern United States.

Rafael Guastavino’s role at Biltmore

George Vanderbilt wanted the very best architects to work on the design of Biltmore House. Rafael Guastavino’s reputation had grown to the point that in 1891 Vanderbilt summoned him to Asheville to work on his mansion.

Guastavino built his trademark lightweight Catalan vaulting in the porte cochere and entrance hall, the Winter Garden corridors, the loggia, the basement’s indoor swimming pool, and the red brick Gate House.

Guastavino’s tile vaulting in the entrance hall of Biltmore house

The indoor swimming pool with its vaulted ceiling and underwater lights

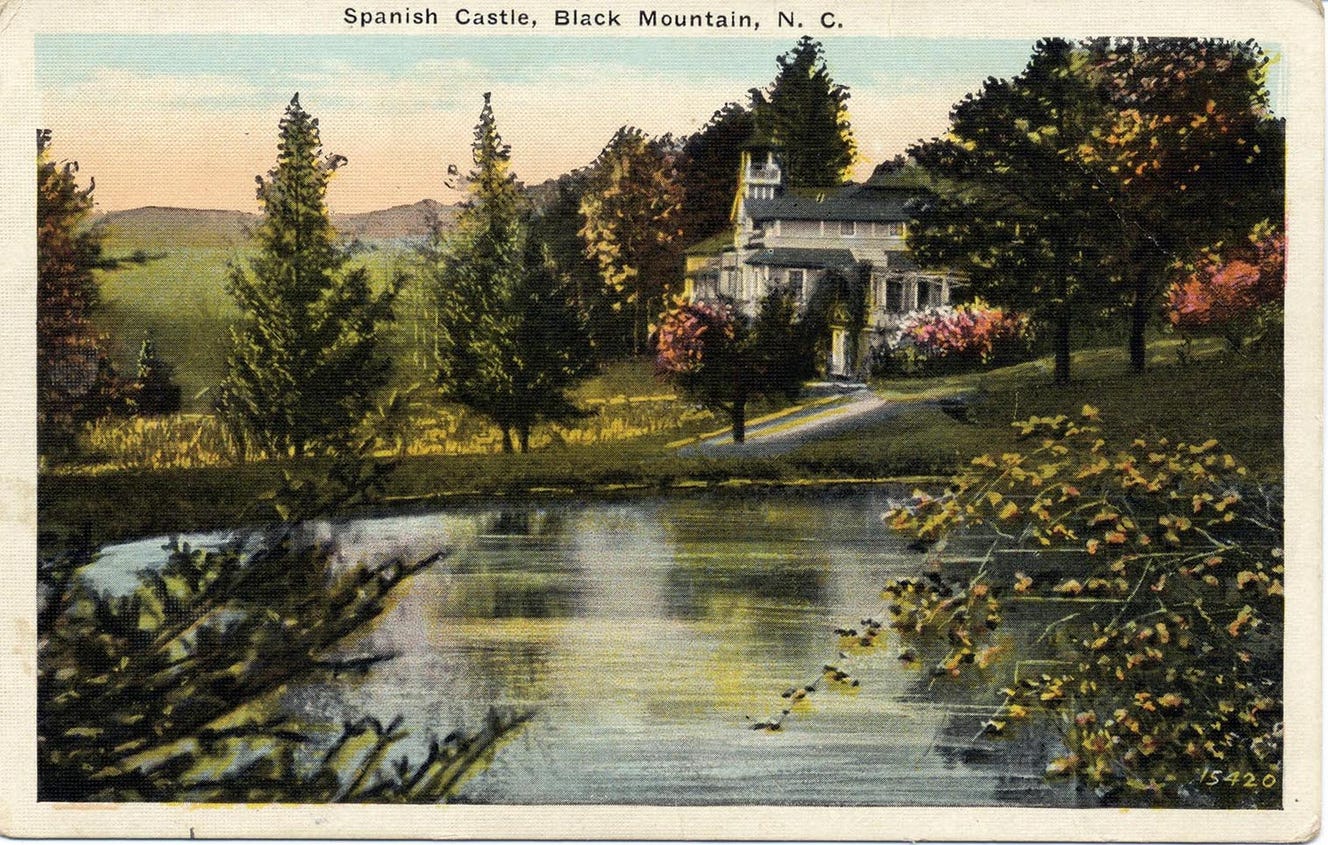

Rhododendron, Guastavino’s estate

While working on the Biltmore Estate, Guastavino also fell in love with the landscape and began to purchase tracts of land in Black Mountain. He left the running of the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company in New York in the capable hands of his son, Rafael Jr. He then built a home on his six-hundred-acre estate and moved there with his second wife, Francesca.

“Guastavino sculpted the place as though it were his own Biltmore Estate,” wrote Jon Elliston for WNC Magazine. He rerouted streams and built dams for small ponds. He built terraces and charted out roads, cornfields, orchards and a vineyard. He commissioned a house, a barn, several other outbuildings and kilns to fire tiles for his company.

“As much as he could afford to, he was creating his own estate,” says Peter Austin, an Asheville native and librarian for Salem College in Winston-Salem. “He had worked for wealthy people in Spain before he came here,” Austin says. “He’d been on plenty of estates, especially ones that were agriculturally based, and that’s what he wanted.”

The “Spanish Castle”

Due to its unique design and exotic residents, Guastavino’s home was known by locals as “The Spanish Castle”. It was a ramshackle three-storey, whitewashed, wooden house with a central bell tower that rang on the hour.

The twenty-five-room mansion included a room for each of Guastavino’s interests.

He was a devout Catholic and built a chapel to pray in. He had been a talented violinist as a young man and built a music room in which to practice. He built a downstairs billiards room for entertaining guests, with a wine cellar nearby. The house was an ongoing work-in-progress that was never truly finished.

In the words of Francesca’s maid, Florence Plemmons:

“For the first few years the first floor was occupied by farm horses until a barn was built for them. After the horses were taken out, the first floor was remodelled into nice rooms for the family,” which included two kitchens, a large dining room, and a billiard room. “The second floor consisted of eleven rooms. First, the chapel room. Mr. Guastavino was a devout Catholic. He went into the Chapel to pray each morning before eating his breakfast. Across the hall [from the Chapel] was a music room with all kinds of musical instruments. He was the finest musician I ever saw in all the years I have lived.”

Guastavino continued his experiments with tile technology on the grounds of Rhododendron. He took advantage of North Carolina’s abundant clay and used the water power supplied by Lakey Creek and his two man-made ponds.

Although no formal landscape plans exist, Guastavino’s property shows the influence of Frederick Olmstead, designer of the Biltmore gardens. The landscape design took advantage of the fan-shaped valley and the irregular terrain to create terraces ornamented by native hardwoods, evergreens, and flowering trees.

The kilns

Guastavino built at least two kilns for manufacturing bricks and tiles, one of which still survives. Its sixty-foot- tall chimney is still intact.

Guastavino used local red clay to manufacture tiles for projects around the country. He also purchased land in the middle of the state, which he mined for white clay. The kiln could fire thousands of tiles at a time, some of which were shipped down the short railroad line to Biltmore, Asheville, and the Basilica of Saint Lawrence.

The proximity of the railroad in Black Mountain meant Guastavino could run his business from the estate. From the turn of the twentieth century, Rhododendron’s address features on the company letterheads.

Rhododendron became Guastavino’s workshop and retreat, a place where he could experiment with arts that were familiar or new to him. He continued to draft innovative designs for far-flung masterpieces and found time to immerse himself in music, socializing, and winemaking. He also forged a deep bond with his second wife, Francesca, a Mexican immigrant who was seventeen years younger than him.

The couple hosted lavish gatherings at their home. One dinner guest, whose name is unrecorded, penned this paean to time spent at Rhododendron:

The poets may sing of the feasts of Lucullus,

Of champagne, and Tokay, and other things fine,

But give me a dish of Mr. Guastavino’s paella,

And a bottle or two of his own pleasant wine.

Rhododendron witnessed far more work than play. At the base of the bell tower, Guastavino inscribed his motto in Latin: Labour Prima Virtus (Labour is the chief virtue).

Francesca marvelled at how her husband, even in his semi-retirement, remained busy. “He seems to get up earlier every day; this morning it was twenty minutes to one!” she wrote in a letter to a family member. “He never seems to slow down.”

Guastavino’s last work - The Basilica of Saint Lawrence in Asheville

The Basilica of St. Lawrence

After completing his work on Biltmore House in 1895, Guastavino was drawn back to Asheville in the early 1900s to collaborate with architect Richard Sharp Smith in building the Basilica of Saint Lawrence.

The Catholic population of Asheville had increased to the point where the St. Lawrence Church was turning people away. Guastavino relished the opportunity to build a new church. He designed everything from the statuary and chapels to the elliptical dome.

The historian Anne Chesky wrote, “By 1903, Guastavino, now semi-retired, began working on his passion project – a Catholic Church designed around a large, free-span elliptical dome. He financed most of the Asheville-based project himself and provided much of the tile, which had been fired in kilns at Rhododendron.”

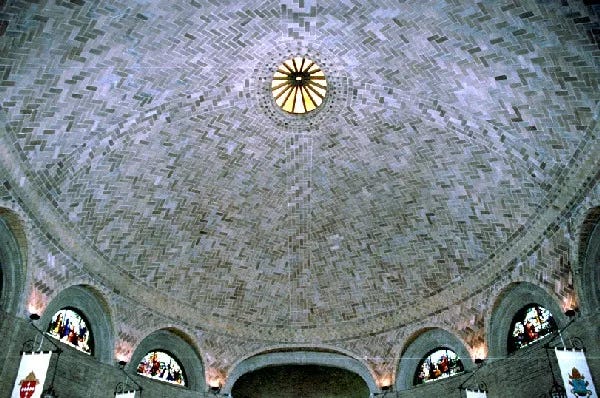

Guastavino’s Spanish Baroque church is crowned by the largest freestanding elliptical dome in North America. The dome’s clear span of 58 by 82 feet is Guastavino’s most impressive achievement

Guastavino and St. Lawrence Church attracted frequent coverage in Asheville newspapers. The Asheville Citizen-Times of October 16, 1909, carried a detailed retrospective of its construction over nearly five years:

“This mighty vault was built bit by bit over nothing, above the church floor. When Mr. Guastavino began preparations of work up there with a handful of men, builders called him foolhardy, said it was an impossible feat, that there was no precedent for it.

“Mr. Guastavino’s plan was to build the entire dome of thin, flat terra cotta tile, 6 x12 inches, and an inch thick—much in size and shape like the bricks of the ancient Romans still to be seen in the walls of the little church near Canterbury, England.

“Mr. Guastavino began laying these tile exactly as if he were shingling an imaginary dome in space, only using cement for nails. Beginning at the bottom course, the first six or seven thicknesses of tile were laid one over the other braking joints, in a special cement of plaster of Paris. The next course, laid in Portland cement, was held in place by overlapping the tile below. The process was repeated until the great dome was finished without the aid of girdlers [sic] or supporting scaffolds.”

The great church was still unfinished in 1908 when Rafael Guastavino died at his home at Black Mountain, at the age of sixty-five, after a bout of lung congestion and kidney complications. A requiem mass was held for him before he was interred in a crypt to the left of the church’s altar.

Rafael Jr. continued his father’s work

Rafael Guastavino Expósito (1873-1950)

Guastavino’s son Rafael Jr. took over the family business. He completed the Basilica of St. Lawrence in 1909, a year after his father’s death. A year later, Rafael Jr. went on to build one of the largest domes in the world for New York’s Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. *

Francesca Gustavino

According to Francesca’s maid, Florence, Francesca Gustavino (1859-1946) “was a native of Mexico, a small, dark complexioned woman with coal black hair that touched the floor when she was standing. Surely her hair was her glory. She was a bit peculiar to be a rich woman. She did not like nice clothes or jewellery. She didn’t wear any jewellery except her wedding ring. She like to dress like the poor mountain people, with patches on her clothes.”

Francesca was deeply devoted to her husband and was shattered by his death at the age of 65. The young socialite dressed in black and became a recluse. “Francesca was desolate,” Guastavinos’ grandson Rafael Guastavino IV wrote. “At the time of his death she had the big clock in the tower above the house stopped. She would never allow it to run again; it was a symbol that, for her, time had stopped.”

Guastavino’s widow continued to reside as a recluse at Rhododendron for another 25 years. She lived in the house until an old stove caught fire and destroyed part of the house. Francesca was badly burned and spent the last three years of her life in an Asheville rest home until her health declined. She passed away in 1946.

Guastavino’s legacy

Fire and weather dilapidated the structure of the fabled Spanish Castle. It was razed in the late 1940s. All that remains of the foundation is a long, low, wall of stone and brick.

Johnson notes the irony. “Here was a man who emphasized the benefits of building with stone and tile - of making nothing but fireproof buildings,” she said. “But because of the expediency and the low cost - he had a lot of forest to log on the property - he made his home out of wood.”

In 1948, Christmount acquired the property as a national retreat and conference centre for the Disciples of Christ. The church has looked after Rhododendron ever since.

Helen Johnson, Christmount’s assistant director and other staffers work to preserve Guastavino’s legacy. Johnson often walks the trails that wind around Rhododendron’s ruins. On a recent stroll, she identified remnants of Guastavino’s time there. In one clearing surrounded by an iron fence sits a heap of bricks - the dome-shaped kiln that collapsed decades ago. Next to the rubble the kiln’s sixty-foot chimney is still standing.

Pieces of tile bearing the distinctive “Guastavino” stamp in the rubble of the collapsed kiln. Photo by Lyss Hunt.

The sixty-foot chimney near the collapsed kiln

At a spot along the retreat’s entrance, Johnson unlocks a wooden door set within brick and stone arches on a sloping hillside.

The entrance to the wine cellar, the only structure on the Rhododendron estate made with Guastavino’s trademark tiling. Photo by Lyss Hunt

Stepping inside, she points out the vaulted ceiling of the hillside wine cellar - made with bricks that bear the Guastavino name. It is the only place on Guastavino’s estate where he used his tile vaulting

Guastavino made cider with apples from the property’s apple orchard. He had special bottles embossed with the estate’s name and shipped cases of cider to friends and family on special occasions.

Inside the retreat’s main office building is a library featuring rare historic photos from the Guastavinos’ heyday, along with samples of bricks, bottles, tiles, and glazes crafted by Guastavino and his son. In 1989, the former estate was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

As time and the elements take their toll, Rhododendron’s physical presence slowly fades. But the place still offers a lasting testament to Guastavino’s life and work.

“There weren’t that many people who came from Spain to the United States at the time he did, and certainly not many of them came to this part of the country,” Austin says. “Guastavino wanted to live in Western North Carolina. His estate gives us a way to connect to other cultures and other ways of doing things.”

The remaining kiln and chimney

Guastavino’s legacy

Rafael Guastavino’s footprint was so deep in New York City that, in his obituary, The New York Times named him the ‘architect of New York’.

In 2014 the Guastavinos triumphed with the exhibition, “Palaces for the People: Guastavino and the Art of Structural Tile” held at the Museum of the City of New York. The exhibition was a well-deserved tribute to the father and son who designed so many of new York’s most iconic buildings.

As often happens, Rafael Guastavino and his son Rafael Jr. are barely recognized in their home country. Despite recent exhibitions and academic interest in his work, Guastavino’s fame is limited to specialized architectural circles. He has not been recognized or as widely celebrated in Spain.

_______________________________________________________________________

Authors note

* For more information about the Church of St. John the Divine you can read my article: Rafael Guastavino and the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, New York

________________________________________________________________________

Acknowledgments

Biltmore photography by Elena Sullivan

Lost To Time: The relics of architect Rafael Guastavino’s estate, Rhododendron, hint at a rich life. Jon Elliston – WNC Magazine. Mountain living in Western North Carolina. March 2012.

Rafael Guastavino and “The Spanish Castle”. Melanie English. Swannanoa Valley Museum. March 2016

Anne Chesky. Asheville Museum of History.

____________________________________________________________________________

If you wish to receive new articles as they are published, you can subscribe to my free Substack: https://architecturalwonders.substack.com

Please feel free to share the link and invite your friends and family to subscribe.

If you have read and enjoyed my article, you can let me know by clicking on the heart icon below. I would also welcome your comments. Thank you for reading!

Fascinating stories of very special people! Thank you Elysoun